The Camarillo State Mental Hospital History Blog

Barred window of the abandoned Camarillo State Mental Hospital (Photo/Copyright: K.Anderberg)

According to the Camarillo State Hospital Archives: "Camarillo State Hospital was touted as the largest psychiatric hospital this side of the Mississippi when it opened in the mid-1930's. "From a mere 410 patients in 1936, the population grew to 1,082 in 1937; 2,501 in 1940, 4,123 in 1945, 4,960 in 1950, 6,748 on April 8, 1953, 6,865 on June 30, 1955, and in excess of 7,000 patients in 1957."

This site is devoted to the history of Camarillo State Mental Hospital, which is located in Camarillo, CA, just north of Los Angeles. The documentation of institutional history is important to protect people in institutions today. I also believe there are serious and important lessons to learn from the study of the "unwanted" in America's past. I received my Master's Degree in Archiving and History in 2010 from CA State University Northridge, and have been working on the documenation of this monolith mental institution's hidden history ever since. It is odd to me that so little has been written about an institution which held 7,000 patients at a time in its heyday. It was open as a mental hospital from 1936 until the 1980's when it changed to be primarily an institution for people with learning/mental disabilities. Currently, the old buildings are being grazed and remodeled, transforming old isolation rooms into dorm rooms, etc. on a new college campus (CA State University Channel Islands).

UCLA's "Research Lab" at the abandoned Camarillo State Mental Hospital...where human experimentation went on for decades. (Photo/Copyright: K.Anderberg)

I began my study of CA institutional history by studying MacLaren Hall, a child protection institution run by Los Angeles County, which was open from the 1940's-2003. Children like me were removed from the custody of dangerous parents/guardians and taken to Mac Hall at all hours of day and night to protect them. I went there at age 8, in 1969, when my parents were failing me as a child. I did a lot of my Master's Degree in History focusing on the history of MacLaren Hall. But Mac Hall's history led me to another CA historical monolith that abused children as well - Camarillo State Mental Hospital. MacLaren Hall was rampant with human rights violations and child abuse, and so was Camarillo State Mental Hospital. Both their children's wards and their adult wards were bastions of abuse. I came to see the similarities between both MacLaren Hall and Camarillo State Hospital and then expanded them out to include many things which are common in all institutions where we have tried to lock away certain people. Authorities from Camarillo State Hospital would raid MacLaren Hall at night and take children from the one institution to the next, experimenting on children like animals. It disturbs me to know what goes on in these institutions due to what I saw as a child. When I began to explore the abandoned Camarillo Mental Hospital in 2010, I had never seen anywhere that reminded me so much of MacLaren Hall. I took a picture of one of the isolation rooms and sent it to some MacLaren Hall survivors I know. One responded, "Ah, yes, it is painted "Pussy Pink" as the janitor at MacLaren Hall used to call it." That one comment sums a lot of this up, really. We were preyed upon inside MacLaren Hall by guards and other inmates, which is exactly what happened at Camarillo Hospital too. This site explores the hidden history of Camarillo State Mental Hospital. I am glad I got into the buildings in their old states before they began refurbishing them into a university campus. I got pictures of many of the original areas at Camarillo Hospital before they were torn down.

Barred windows and doors of the abandoned Camarillo State Mental Hospital (Photo/Copyright: K.Anderberg)

One thing I learned from being a child survivor of a state institution with questionable methods is the history of institutions is well hidden and even outright denied often.

As a child, I tried to tell people about the abuses of children in MacLaren Hall that I saw, and no one wanted to hear it. I tried to talk to people about what I saw in Mac Hall again in my teens,

and even into adulthood, and repeatedly I was told by therapists that 1) MacLaren Hall did not exist, and/or 2) if it did exist, I was never in it, and/or 3) if it did exist, and I was in it,

it was not as bad as I said. But the truth is, MacLaren Hall DOES exist, and I WAS in it as a child and it was WORSE than anything I have been able to describe in words, as you do not get the

sounds and smells and sights with my words and memories.

It was not until I was in my 30's that I was able to find a therapist who believed me about MacLaren Hall. He said that I could not have

made up such detail about something imaginary. He told me to draw what I remember of it. This terrified me, as if drawing it would bring it back to life. It took me months to get the courage to

draw Mac Hall, but finally I did and it was quite liberating, making me feel like finally I was in control of it. My therapist encouraged I write an article about MacLaren Hall so I did, in 2001.

All of a sudden, a ton of other survivors of Mac Hall wrote me emails, telling me that my words and experienced reflected theirs and many said they had never spoken about it to anyone. I went to get my

Master's Degree with one purpose in mind: to learn how to document institutional history against the wills of the institutions and governments who ran them. I actually know a lot about how to

document the history of institutions in a professional manner, without the help of the state or institution, which is a special skill set, for sure. So my work researching Camarillo State

Hospital's past is being done in the same manner I studied Mac Hall. I am going into legal documents, public archives and old newspaper archives to document what people for decades have tried to pooh-pooh.

I am hoping by lending an independent professional historian (as in not paid by the University or state) to the case of Camarillo State Hospital's history, something which has not been done before, I can begin to amass EVIDENCE, documented information

beyond hearsay, about this huge hospital which housed 7,000 patients at a time in the 1950's. The fact that so little can be found about this hospital angers me in the same way I am mad that Mac Hall

was and still is hidden from view on the whole. I feel it is absolutely important that we take the veil off of the history of Camarillo State Mental Hospital. Every time I try to talk

about Camarillo Hospital's past, I get a wrath of ex-employees saying I am making up the things I am saying about Camarillo Hospital's past. Ah, but that is where my Master's Degree comes in. No, I learned

back with Mac Hall history, that it is important to document anything you say about institutional history, so although some of the ex-employees may be very uncomfortable about talking about

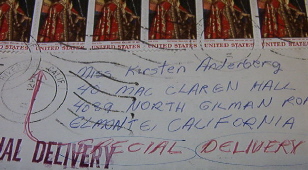

Camarillo Hospital's past, the fact is - I document every single thing I say about its history with credible sources. Letter addressed to K. Anderberg when she was 8 years old in 1969, inside MacLaren Hall, due to child abuse issues with her parents and police...

Letter addressed to K. Anderberg when she was 8 years old in 1969, inside MacLaren Hall, due to child abuse issues with her parents and police...

After studying Camarillo Hospital's history, I am unable to verify that all of the patients were actually "crazy," but I am able to verify some very insane staff worked there. Reading

the Grand Jury indictments, the news headlines, Wilma Wilson's "They Call Them Camisoles," etc., over decades of materials, I can see that the staff at Camarillo Hospital most certainly consisted of people I do not consider mentally stable or appropriate

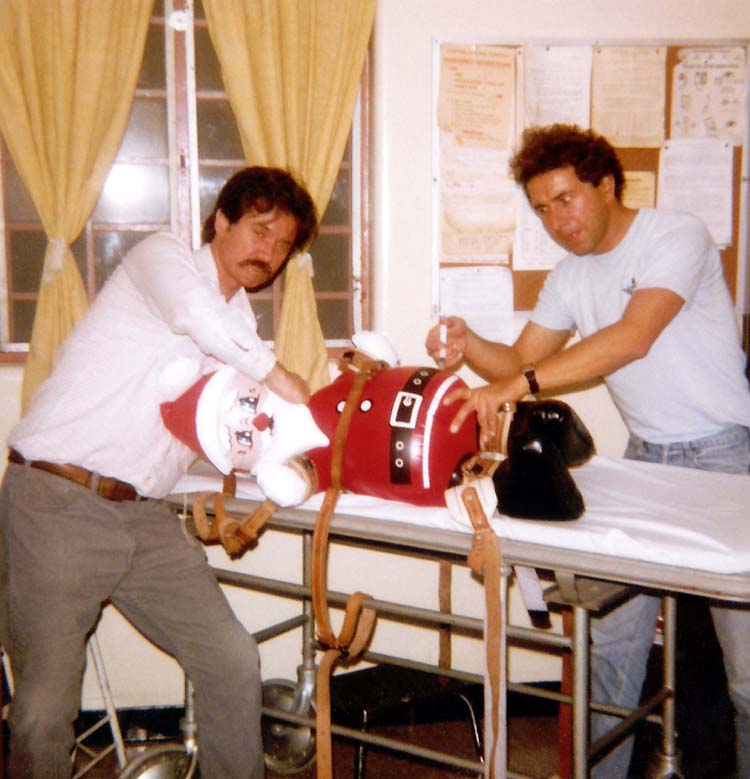

to handle patients. Case in point: This above photo was proudly posted on the Camarillo Hospital Ex-Employees' website, with the caption noting this was "Bob Malloy and Jon Pope" in 1983. Perhaps

this is considered fun and games to ex-employees Bob Malloy and Jon Pope, but I think it reflects mental illness on the part of the staff. Once I brought attention to this photo, that website

quickly took it down, so apparently they, too, see how inappropriate it is, but if I had not brought attention to it, it would be still up on their site for all to see as if it is a great fun

memory of time spent working at Camarillo Hospital. I understand there were qualified nurses and staff, who did care about patients at Camarillo Hospital, but it would be a flat out lie to

say that there were not rampant aides and staff who were abusive to the patients as well. The problem with institutions is the staff attracts people who are abusive because they know these are

people no one cares about, and people no one believes, so they can do anything they want to them, with no accountability. Those kinds of places attract pedophiles and sexual abusers, in addition

to saddists. I saw it as a child in Mac Hall as guards raped children there, and I know it was true in Camarillo Hospital too. The look on the face of the guy holding Santa down in this pic horrifies me.

Ex-Camarillo Hospital employees Bob Malloy and Jon Pope in 1983, from a picture posted on an ex-staff site from the hospital, looking back at the "fun" they had working there...

I have studied institutional history to understand both MacLaren Hall and Camarillo State Mental Hospitals better. Here are some links to important works in the area of Institutional History:

* Titicut Follies: In 1967, a journalist filmed the inside of the Bridgewater Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Bridgewater, Mass. When it was entered at indy film festivals, the State of Mass. took

the film makers to court and got the film banned from public viewing based on "patient confidentiality." It was not until 1987 that a court finally overturned the ruling and made it possible to view this

important documentary about insane asylums.

*

* Michel Foucault's "Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason," as well as his

"Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison," are phenomenal books which analyze the mindset and history of prisons, mental asylums, poor houses, work houses and the Elizabethan Poor Laws which

try to separate the worthy and unworthy poor...

* "The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases From a State Hospital Attic" is a telling documentation of

patients from the 120+ year old Willard Mental Asylum in NY

* PBS' American Experience: "The Lobotomist" follows the reckless and insane career of Dr. Walter Freeman, the father

of the lobotomy, which was later banned in all 50 states.

* "Keeper of the Keys" by Nadine Scolla, was originally posted on the Camarillo Mental Hospital Archives website, but

since people began to apparently use their website, and read "Keeper of the Keys," in their never-ending attempt to cover up the hospital's history, the archive has since hidden their copy of this

book which was reportedly written about Camarillo Mental Hospital. Thank goodness, others have copies and have posted them online. This book is shocking and horrifying, but as you can see in

my book, "They Call Them Camisoles - Revisited," I connect the words of Nadine Scolla with those of Wilma Wilson, as well as grand jury indictment evidence, and you can see a running theme throughout

of abuse.

Olivia DeHavilland was nominated for an Academy Award for

her portrayal of Virginia Cunningham in the 1940's movie "The Snake Pit." In this photo, she is receiving hydro-shock treatments in the movie. The 1948 movie, "The Snake Pit," was filmed on

the grounds of Camarillo State Hospital, and due to its disturbingly realistic portrayal of what goes on in mental institutions, 26 states changed their mental health laws

after the movie became popular.(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Snake_Pit) Some of the more marked changes to come from the changes the movie inspired were people no longer being locked up indefinitely

without some opportunity for reviews of their cases, and nonconsentual psychiatric treatment came under much greater scrutiny, as did the treatments. In a 1986 L.A.Times article entitled,

"Mental Hospital Sheds Image of Grim "Snake Pit"," James Quinn writes, "In the 1950s, Camarillo State Hospital, like most mental institutions of the day, was a massive warehouse

for the mentally ill, its drab wards bulging with more than 7,000 patients, most of them committed for years or for life. Crowding was so severe that many patients were forced to sleep

on mattresses in hallways and to wait in line to use bathrooms or exercise areas, veteran employees said. Little effort was spent on treatment. Then as now, the huge hospital

had the deceptive appearance of a college campus. The Mediterranean-style facility, with more than 40 buildings, sprawls over manicured grounds and is surrounded by lush farm

fields four miles south of the Ventura Freeway. The facility has never been completely fenced." The article goes on to speak of conditions in the 1980's: "The large hospitals were once dubbed "snake pits"-

a term borrowed from the 1948 film "The Snake Pit," which painted a bleak picture of life in the nation's mental hospitals. Now, instead of being confined for years or for life,

patients at Camarillo are hospitalized for an average of only three weeks, then discharged or transferred to local mental health centers or board-and-care facilities. As a result, the hospltal's count

of mentally ill patients has dwindled to 644, less than a tenth of its peak volume, said a hospital spokesman." (James Quinn, L.A.Times, "Mental Hospital Sheds Image of Grim "Snake Pit"" (March 9, 1986), p. V_A4).

Olivia DeHavilland was nominated for an Academy Award for

her portrayal of Virginia Cunningham in the 1940's movie "The Snake Pit." In this photo, she is receiving hydro-shock treatments in the movie. The 1948 movie, "The Snake Pit," was filmed on

the grounds of Camarillo State Hospital, and due to its disturbingly realistic portrayal of what goes on in mental institutions, 26 states changed their mental health laws

after the movie became popular.(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Snake_Pit) Some of the more marked changes to come from the changes the movie inspired were people no longer being locked up indefinitely

without some opportunity for reviews of their cases, and nonconsentual psychiatric treatment came under much greater scrutiny, as did the treatments. In a 1986 L.A.Times article entitled,

"Mental Hospital Sheds Image of Grim "Snake Pit"," James Quinn writes, "In the 1950s, Camarillo State Hospital, like most mental institutions of the day, was a massive warehouse

for the mentally ill, its drab wards bulging with more than 7,000 patients, most of them committed for years or for life. Crowding was so severe that many patients were forced to sleep

on mattresses in hallways and to wait in line to use bathrooms or exercise areas, veteran employees said. Little effort was spent on treatment. Then as now, the huge hospital

had the deceptive appearance of a college campus. The Mediterranean-style facility, with more than 40 buildings, sprawls over manicured grounds and is surrounded by lush farm

fields four miles south of the Ventura Freeway. The facility has never been completely fenced." The article goes on to speak of conditions in the 1980's: "The large hospitals were once dubbed "snake pits"-

a term borrowed from the 1948 film "The Snake Pit," which painted a bleak picture of life in the nation's mental hospitals. Now, instead of being confined for years or for life,

patients at Camarillo are hospitalized for an average of only three weeks, then discharged or transferred to local mental health centers or board-and-care facilities. As a result, the hospltal's count

of mentally ill patients has dwindled to 644, less than a tenth of its peak volume, said a hospital spokesman." (James Quinn, L.A.Times, "Mental Hospital Sheds Image of Grim "Snake Pit"" (March 9, 1986), p. V_A4).

Camarillo State's HydroTherapy/HydroShock Treatment Equipment/Room, Ward 26, South Quad (Photo: K. Anderberg, August 8, 2010)

Camarillo State's HydroTherapy/HydroShock Treatment Equipment/Room, Ward 26, South Quad (Photo: K. Anderberg, August 8, 2010)

At Camarillo, ground-breaking cures for insanity were claimed to have been discovered, while Camarillo was simultaneously being accused repeatedly and constantly of patient abuses and

negligent deaths. Most of their more celebrated treatments such as lobotomies, electroshock treatments, hydrotherapy shock treatments, isolation in restraints, etc. were later found

to be inhumane and have since been banished. Electroshock therapy ended in the 1970's at Camarillo, and the hospital finally closed as a hospital, amidst grand jury investigations, in 1997.

This is a photo of a woman's ward at Camarillo State Hospital on January 28, 1949: I am unsure as to the photographer. The women's faces are

whited out for patient confidentiality issues. As you can see, there are beds lined up against each wall, and then women also lined up in chairs down the middle, due to not enough beds. This

room is similar to ones I have photographed at

Camarillo now that it is abandoned. I recognize the end walls always having that weird opening, in this pic, it is just to the left of the woman attendant. Below is a photo of a similar

room at the abandoned Camarillo site.

This is a photo of a woman's ward at Camarillo State Hospital on January 28, 1949: I am unsure as to the photographer. The women's faces are

whited out for patient confidentiality issues. As you can see, there are beds lined up against each wall, and then women also lined up in chairs down the middle, due to not enough beds. This

room is similar to ones I have photographed at

Camarillo now that it is abandoned. I recognize the end walls always having that weird opening, in this pic, it is just to the left of the woman attendant. Below is a photo of a similar

room at the abandoned Camarillo site.

This is a photo of an old ward room at Camarillo, as it looks now in 2010. This unit was built in 1937. Note identical markings on this photo to the one above. The same

ceiling, the door, the vent above, and the opening below

in the middle of the end walls, and the windows with bars, and shape of room, all the same as the photo above. This is Ward 28 in the South Quad. (Photo: K. Anderberg, Jan. 21, 2010)

This is a photo of an old ward room at Camarillo, as it looks now in 2010. This unit was built in 1937. Note identical markings on this photo to the one above. The same

ceiling, the door, the vent above, and the opening below

in the middle of the end walls, and the windows with bars, and shape of room, all the same as the photo above. This is Ward 28 in the South Quad. (Photo: K. Anderberg, Jan. 21, 2010)

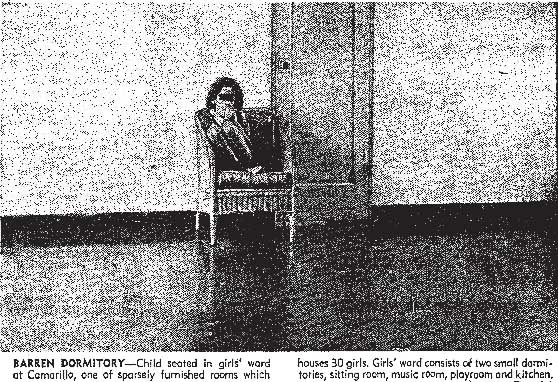

This photo is from an L.A.Times dated Aug. 26, 1955. The caption reads "Barren Dormitory: Child seated in girls' ward at Camarillo, one of sparsely furnished rooms which

houses 30 girls. Girls' ward consists of 2 small dormitories, sitting room, music room, playroom and kitchen."

This photo is from an L.A.Times dated Aug. 26, 1955. The caption reads "Barren Dormitory: Child seated in girls' ward at Camarillo, one of sparsely furnished rooms which

houses 30 girls. Girls' ward consists of 2 small dormitories, sitting room, music room, playroom and kitchen."

The abandoned buildings at Camarillo State Hospital reflect the severity of the institution. Layers of grates, bars, and locks are on everything...we took this photo

in the South Quad on Feb. 21, 2010.

The abandoned buildings at Camarillo State Hospital reflect the severity of the institution. Layers of grates, bars, and locks are on everything...we took this photo

in the South Quad on Feb. 21, 2010.

The first buildings on site at the Camarillo Hospital were what later became known as "The House of Style," and also the Unit 11 building, both built in 1934. In 1935, the Bell Tower building was built, and in 1936 the kitchen and dining area was added to the South Quad, and in 1937, the rest of the South Quad buildings, all of those pictured on this page (but for the one picture of a grate from the North Quad), as a matter of fact, were built. The south portion of the North Quad was built next, in 1940, and then the northeast side of the North Quad was built in 1941. In 1950, a small part of the southwest side of the North Quad was built, then in 1951, the Receiving and Treatments building was added to the eastern end of the campus, and the northwest side of the North Quad was finished. Therefore, the buildings that are the oldest are in the South Quad, then the south end of the North Quad, then the North end of the North Quad and the RT Building.

South Quad...Much of the old Camarillo State Hospital grounds were set up with these small isolated courtyards, such as you see in this photo. The gate in this photo is open, but during Camarillo's time as a hospital, it was locked with a heavy metal gate. (Photo: K. Anderberg, Jan. 21, 2010)

In the 1970's, Camarillo routinely overdrugged incoming patients with something they simply referred to as a "Number 1," which was mixed shots of Thorazine, Stelazine and Hyosine, or Serentil, Stelazine and Hyosine, according to a Nov. 17, 1976 L.A.Times article by Ellen Hume. This tranquilizer cocktail was discontinued in March 1976, due solely to people dying from it and grand jury inquisitions as to the circumstances of suspicious patient deaths at Camarillo. (Ellen Hume, L.A. Times, "Mental Hospital Shift on Drug Policy Told," (Nov. 17, 1976), p. OC1). In a 1976 Times article entitled, "Deaths Investigated at State Mental Hospital," Michael Seiler wrote, "The Ventura County district attorney is investigating more than 100 deaths at Camarillo State Hospital over the last three years and charges of murder or manslaughter may be filed by the end of the year, a spokesman for the district attorney's office said Monday. Asst. Dist. Atty. Michael Bradbury said his office is "looking hard" at 79 of the deaths, including cases of drug overdoses, strangulation and possible gross negligence by hospital staff. "lt's our present intention to take the case to the grand jury," Bradbury said. The probe was opened early this year after the district attorney's office had determined that some deaths at the state mental hospital had occured under "unusual circumstances," Bradbury said. It is the second investigation of Camarillo to come to light in 1976. Earlier, a state Health Department task force looked into allegations of inadequate care, unsanitary conditions, heavy drugging of patients and general mismanagement in childrcn's units of the hospital, and then ordered corrections. No changes have been filed in connection with the state probe. The Ventura County Probe includes examinations of the deaths of both children and adults, Bradbury said." (Michael Seiler, L.A. Times, "Deaths Investigated at State Mental Hospital," (Oct. 12, 1976), p. 1).

To learn more about the daily life inside Camarillo Hospital as a patient, check out "They Call Them Camisoles - Revisited."

This book takes a new look at Wilma Wilson's classic book, "They Call Them Camisoles," which was published in 1940. Wilma was committed to Camarillo State Mental Hospital for 4 months for alcoholism in 1939 and wrote a book about her time there. This book includes the entire text and all sketches from the book "They Call Them Camisoles" with a new addition of over 150 photographs of the places Wilma speaks of in the hospital, taken by K.Anderberg. This book also includes references to L.A.Times articles that illustrate what Wilma has written, as well as providing a history of the hospital. "Keeper of the Keys," a book published in 1976 by a Camarillo nurse, about abuses at the hospital, is also compared and contrasted to Wilma's words throughout this book. A look into Wilma's life before going to Camarillo is explored through CA birth and census records, in addition to newspaper reports, and her sensational death is also followed through news reports in the end of this book. (You can also get this

book in Ebook format at

http://www.amazon.com/They-Call-Them-Camisoles-Revisited-ebook/dp/B00A3W9W04/.)

This book takes a new look at Wilma Wilson's classic book, "They Call Them Camisoles," which was published in 1940. Wilma was committed to Camarillo State Mental Hospital for 4 months for alcoholism in 1939 and wrote a book about her time there. This book includes the entire text and all sketches from the book "They Call Them Camisoles" with a new addition of over 150 photographs of the places Wilma speaks of in the hospital, taken by K.Anderberg. This book also includes references to L.A.Times articles that illustrate what Wilma has written, as well as providing a history of the hospital. "Keeper of the Keys," a book published in 1976 by a Camarillo nurse, about abuses at the hospital, is also compared and contrasted to Wilma's words throughout this book. A look into Wilma's life before going to Camarillo is explored through CA birth and census records, in addition to newspaper reports, and her sensational death is also followed through news reports in the end of this book. (You can also get this

book in Ebook format at

http://www.amazon.com/They-Call-Them-Camisoles-Revisited-ebook/dp/B00A3W9W04/.)

I took this picture at the Camarillo State Mental Hospital on March 7, 2013, using my Kindle Fire. I placed it up to the window above me, and clicked. I could not see inside the window when I took the photo.

This was in the area that was supposedly the forensic court room, according to one historian I have met, but others have said it was a medical office area, I am not sure what it was, but it is

in that last building before you turn to the right off the main road into the school, with the bars on the porch, now abandoned. The pink bar across the top of the photo is one of the typical bars on the windows at Camarillo Hospital. But I was shocked

when it looked like a nurse in the picture! There is also a shadow which looks like someone in a wheelchair next to the partial nurse! I have not doctored this photo in any way but to reduce its size.

It is just how I took it. It sure looks like a nurse in there, or part of a nurse, missing arms, but the uniform is there...although the doors are

locked, no one was inside and the buildings are abandoned. After exploring the old Camarillo State Mental Hospital, I began to believe in ghosts...(Photo/Copyright: K.Anderberg, 2013)

Unit 28, solitary/isolation units at Camarillo State Mental Hospital. This ward was built in 1937 and housed psychiatric patients. There were many incidents of patients dying in restraints, heavily drugged, left alone in these isolation rooms. Barely large enough for beds, many of these rooms still have curtains in them, and this photo shows how close together the rooms were. Back when this unit was overcrowded, we are sure noise came out of these rooms, even when the doors were locked, thus you would *hear* your neighbors, even if you did not see them. (Photo: K. Anderberg, Jan. 21, 2010)

In another sad testament to Camarillo's incompetence and danger to its patients, a Nov. 16, 1976 L.A. Times article writes that Thomas Riddle, 37, had committed himself to Camarillo's drug and alcohol treatment

center for detoxification, yet two hours after he was admitted in Nov. 1976 as a patient, he was "found dead, shackled at the hands and feet in an isolation room at Camarillo's acute psychotic ward." The autopsy

said he died from "asphyxia due to compression of the neck and multiple drug overdose." Apparently the patient was full of vodka, methadone, valium, and barbituates when he was

admitted but the staff did not check for other drugs in the system before they gave him a "Number 1" cocktail of heavy tranquilizers including Serentil, Stelazine, and Hycocine to "subdue the patient." The article says "Riddle was subdued

by five hospital employees, locked into leather cuffs, and tied down to a wheelchair. He was wheeled to the acute psychiatric ward." The staff "psychiatric technician" on duty that night, Mr. Borel,

told the grand jury that "he did not feel there was enough staff on the ward to subdue the patient without the heavy tranquilizers." The psychiatric technicians on duty that night all testify that

no one choked the patient or went near his neck, yet the autopsy shows someone constricted his airflow at his neck. (Ellen Hume, L.A.Times, "Tranquilizers Linked to Death of Patient" (Nov. 16, 1976), p. B3) In an L.A.Times article published one day after the one just cited, more

information emerged. "only one witness, psychiatric technician Ronald Willis, failed to deny having seen a "bar strangle hold" or choke hold at the hospital. Such holds

allegedly are used in some mental facilities to subdue patients." When Willis was asked if he had ever used the hold on a patient, or seen others use it on patients at Camarillo,

he twice pleaded the 5th Amendment, saying it could incriminate him. (Ellen Hume, L.A. Times, "Mental Hospital Shift on Drug Policy Told," (Nov. 17, 1976), p. OC1).

In an attempt to understand *who* exactly was inside Camarillo Mental Hospital, I spent many months combing through archives to find women's names and stories that led them to Camarillo Hospital. I put together many

women's names and stories in a book entitled, "Commitment Criteria I" which is available in both Kindle and

paperback formats. Here is the book's description: "Follow 23 women's paths into Camarillo State Mental Hospital in California. (Camarillo Hospital was open from 1936-1997 and in its heyday, housed 7,000 patients at a time.) Due to its proximity to Los Angeles, Camarillo Hospital had an abnormal amount of Hollywood connections. Life stories in this book range from the criminally insane to women who were committed due to controlling husbands. In this first volume, 23 women's stories are told, including those of Marilyn Monroe's mother, Comedian Bob "Bazooka" Burns' daughter, Actress Gia Scala (who starred in movies with Glenn Ford, Gregory Peck and more), Edward G. Robinson's daughter-in-law, Silent film actress Catherine Smith, Actress and race horse stable owner Paula Stanway Thorpe, One of the first women run for CA governor Hazel Younger, Ex-wife of Diamond Walnut Growers Inc.'s founder, and the 4th woman gassed to death in CA's then 111 year history of the death sentence by gas chamber. These stories range from 1942-1986. Includes 22 photographs of the abandoned hospital taken by the author. These photographs have never been published in a book before."

In an attempt to understand *who* exactly was inside Camarillo Mental Hospital, I spent many months combing through archives to find women's names and stories that led them to Camarillo Hospital. I put together many

women's names and stories in a book entitled, "Commitment Criteria I" which is available in both Kindle and

paperback formats. Here is the book's description: "Follow 23 women's paths into Camarillo State Mental Hospital in California. (Camarillo Hospital was open from 1936-1997 and in its heyday, housed 7,000 patients at a time.) Due to its proximity to Los Angeles, Camarillo Hospital had an abnormal amount of Hollywood connections. Life stories in this book range from the criminally insane to women who were committed due to controlling husbands. In this first volume, 23 women's stories are told, including those of Marilyn Monroe's mother, Comedian Bob "Bazooka" Burns' daughter, Actress Gia Scala (who starred in movies with Glenn Ford, Gregory Peck and more), Edward G. Robinson's daughter-in-law, Silent film actress Catherine Smith, Actress and race horse stable owner Paula Stanway Thorpe, One of the first women run for CA governor Hazel Younger, Ex-wife of Diamond Walnut Growers Inc.'s founder, and the 4th woman gassed to death in CA's then 111 year history of the death sentence by gas chamber. These stories range from 1942-1986. Includes 22 photographs of the abandoned hospital taken by the author. These photographs have never been published in a book before."

Strange ornate metal grates are in Unit 30 in the South Quad, inside the door, looking up to the second floor. It seems this grate is

bolted to the wall, and perhaps was there to prevent patients from leaping or falling over the banister onto the stairs. (Photo: K. Anderberg 21/Feb/2010)

Strange ornate metal grates are in Unit 30 in the South Quad, inside the door, looking up to the second floor. It seems this grate is

bolted to the wall, and perhaps was there to prevent patients from leaping or falling over the banister onto the stairs. (Photo: K. Anderberg 21/Feb/2010)

On Nov. 13, 1976, in the L.A.Times, Ellen Hume wrote, "more horror stories about staff shortages, the mixing of dangerous drugs and possible incompetence of some employees at Camarillo State Hospital emerged Friday in the 4th day of public hearings before the Ventury County grand jury." One of the cases cited in this article was the death by starvation of Steven Miller, 33, who died at Camarillo in Sept. 1974. The man in charge of the ward the night Miller died said to reporters that the ones to blame for Miller's death were "your senators, your Dept. of Mental Health, and your governor." He also said there is "just too much paperwork." In another case from the same Nov. '76 article, a "30 year old retarded patient" died on June 8, 1975 by "choking on her own vomit, after the nursing staff tried for 24 hours to get a staff doctor to look at her. The nurses said the patient had gained 15 pounds in 4 days due to drinking water, and eventually the patient died before the doctor showed up to help. This 1976 grand jury was investigating 13 suspicious deaths at Camarillo since 1973, over a 3 year span. Also cited in this article, in 1974, "20 year old Michael Rogers, also a mentally retarded patient, died. The testimony from Camarillo staff said that the patient had two "superficial lacerations" on his face, and when the staff went to stitch them up, the patient panicked and "five male employees struggled to hold him down," and he then went into cardiac arrest and died. The autopsy said his cause of death was he choked on his vomit, and the staff on charge that night says if they had it to do over, they would have put him in restraints, not tried to hold him down with people. After studying the patient's chart, it was found that the night Rogers died he was given an alarming cocktail of drugs from Dr. Moore, on duty that night. Dr. Moore gave Rogers Thorazine, Hyosine, Repoise, antihistamines, antiepileptic drugs and other tranquilizers, and the Physicians Desk Reference of 1974 warns about mixing some of those drugs together. Dr. Moore testified to the grand jury that Hyosine had been banned at Camarillo three months prior and that it may have been found to be linked to deaths. (Ellen Hume, L.A. Times, "Problems with Staff, Drugs Cited at Camarillo Hearing," (Nov. 13, 1976), p. B1).

In an L.A. Times article (Los Angeles Times, "Insulin Rocks the Foundations of Reason and Yet Seems to Restore Sanity in Many Cases," Mar. 24, 1940, p. 16) from 1940, a frightening graphic is displayed, showing first a large hand with an insulin vial in it, and a syringe next to the hand, then below this image is a photo of a blindfolded patient with a nurse holding a flask with tubes coming out of it and doctor over him in a bed, and the doctor is injecting him with a syringe. The caption to this picture says, "The insulin is injected. In a short while a sort of mental earthquake will shake the patient's brain. Attendant Clement handles hypo and Nurse Lewis the flask." Further down the page, more alarming images appear, showing a man with an IV in his arm, and the caption, " Nurse Lewis administers termination treatment, a solution of glucose (sugar) and salt." The next frame shows someone writing on a pad of paper and the caption says, "the charts are checked constantly so that no mishap will occur. The shocks are severe." Then the final photo shows a blindfolded patient in a bed with a tube going into his nose and the caption reads, "to reduce the patient's nightmarish convulsions sedatives are administered by Nurse Leah Lewis."

This article says Dr. Jacob P. Frostig, one of the world's greatest authorities on insulin shock treatment, came to Camarillo in Sept. 1939, after studying insulin treatment with its creator, at the Psychiatric Hospital in Warsaw, Poland. Insulin treatments consisted of a series of shots of insulin which lowered the blood sugar, producing a coma, during which time the doctors said the patients were "shocked" back to mental health. The Times reported in 1940 that Camarillo had an insulin ward which held about 40 beds, separating men from women with a screen in the center. Patients were given a light breakfast at 6:30 AM, and then began injections of 10-500 units of insulin. The Times reports, "The first effects of the drug are drowsiness and excessive perspiration. In the second hour, the consciousness grows cloudy and the body becomes restless. In the 3rd hour, the patient sinks into a deep stupor, often crying out, twisting and writhing. Gags are affixed to prevent him from biting his tongue or lips. The coma deepens and the spasms continue in the 4th hour. Saliva pours from mouth and nostrils. In the 5th and final hour, a rubber tube is inserted into the nose while the patient is still unconscious and fixed in place with adhesive tape. Then the termination treatment is administered and the stomach is flooded through the tube with a solution of glucose (sugar) and salt. The glucose counteracts the effect of the insulin and the patient awakens quickly. The salt is administered to replace losses to the body by perspiration." These treatments would continue on for 5 days, and on the 6th day, the patient was watched closely, then on the 7th day the patient "rested." This would go on for several weeks at a time. The minimum was 15 shocks per patient, and the maximum amount of shocks administered per patient was 50, according to Camarillo doctors. Doctors found after 50 shocks, there needed to be lapses of 3 months in between treatments for the 2nd or 3rd cycle of treatment to work. The insulin ward is described by the Times as having white cabinets on rollers with "EMERGENCY" in big red letters on them. Inside the cabinets were reportedly syringes of glucose, sedatives and adrenaline for emergencies.

In his first 6 months at Camarillo, Dr. Frostig finished treatments on 29 patients, with 23 discharged as cured, 4 being reported as partially recovered, and one who showed some improvement and another who "failed to benefit" and was "pronounced hopeless." In Mar. 1940, Dr. Frostig was treating 36 more patients at Camarillo, hopeful for similarly high rates of recovery. The insulin therapy was said to need 2 years in some cases, but if a patient did not respond within 2 years, he was deemed "hopeless." The Times asks the question, "Does insulin therapy cure insanity permanently?" Dr. Frostig answers "it does, and recurrences rarely happen in cases where the cure is thorough and complete."

Locked window at Camarillo Hospital...(Photo: K.Anderberg)

Locked window at Camarillo Hospital...(Photo: K.Anderberg)

The Times reported in 1940 that most of the 200,000 mental asylum patients in the U.S. fall into two categories; schizophrenia and manic depression. The Times reported that of the 21,884 patients in CA State mental hospitals, 52% were schizophrenics, 10% were manic depressives and the rest were alcoholics and syphilitics. Dr. Frostig said schizophrenics change personalities and become more "seclusive." He said the schizophrenic becomes a hermit and experiences a gradual degradation of all mental capacities. Frostig said that manic depressives are emotionally unbalanced, and suffer from long periods of either elation or sadness. Frostig claimed that insulin treatment could cure both, as long as the conditions had not had enough time to get a "head start." Dr. Frostig also reportedly used Metrazol, a "powerful stimulant producing violent shock and convulsions" on patients but he said he felt insulin was safer. In Spring of 1940, Frostig left to Stockton State Hospital to set up the second insulin therapy unit in the state. Frostig proclaimed he would devote his life to insulin therapy and the treatment of the mentally ill.

Unit 26: Room at Camarillo State Mental Hospital. This ward was built in 1937 and used for "psychiatric treatments." I took this photo on January 22, 2010. The dark lines on the walls are the shadows from the

bars on the windows. There is a light on the wall at the height of a bed, and these lights are in many of the rooms on this ward. This room is only as wide as the left side of the

door in the photo.(Photo: K. Anderberg)

A clip from an N'Sync video filmed at Camarillo. Note the light on the right wall is same type as the one on wall in photo above...those wall lights

are in many of the rooms still. N'Sync filmed a video for their song, "I Drive myself Crazy," at Camarillo after it closed. The video has some good

shots of the inside of the institution.

A clip from an N'Sync video filmed at Camarillo. Note the light on the right wall is same type as the one on wall in photo above...those wall lights

are in many of the rooms still. N'Sync filmed a video for their song, "I Drive myself Crazy," at Camarillo after it closed. The video has some good

shots of the inside of the institution.

Looking in the Los Angeles Times archives, we can see that a wide swath of society ended up in Camarillo State between the year it opened in 1936 until 1997, when it finally closed: teenagers, women who rebelled, men who drank and did drugs, the criminally insane, the questionably insane, sometimes even just people who did not speak English ended up there, as reported by Nadine Scolla, in her book about being a nurse at Camarillo entitled Keeper of the Keys...It is also clear from these archives that brutality and deaths haunted Camarillo throughout its years. An L.A.Times article from Nov. 11, 1976, has the headline, "Hospital Laxity May Have Caused Deaths." The article says in Sept. 1974, A. Cross, 35, "died of smoke inhalation in a small "seclusion room" after apparently setting fire to his sheets with matches." The psychiatric technician on duty that night, Francis Hartwell, said that he and one other nurse were the only ones supervising 45 patients that evening, and according to the hospital rules there should have been at least 4, he said. Additionally Hartwell said he was pulling his second 8 hour shift in a row that evening. Hartwell testified in front of a Grand Jury that "staffing is not proper so you can't assure a safe (shift) out there." The night that Cross died, testified Hartwell, he was "kind of disoriented and disturbed," and "roaming the halls," and then he testified that "the patient accepted medication to calm him down and agreed to sleep in a private seclusion room." Hartwell said he "believed" he had taken the matches and cigarettes away from the patient before placing him in the seclusion room, but the fire inspectors found two cigarette butts and burned matches on Cross' floor after the fire. (Ellen Hume, L.A. Times, "Hospital Laxity May Have Caused Deaths," (Nov. 11, 1976), p. B3).

This is a view of what used to be the farm lands of the Camarillo State Mental Hospital as it looks today in 2010. This is taken from the road leading onto the grounds,

which are to the left. (Photo: K. Anderberg, Feb. 22, 2010)

This is a view of what used to be the farm lands of the Camarillo State Mental Hospital as it looks today in 2010. This is taken from the road leading onto the grounds,

which are to the left. (Photo: K. Anderberg, Feb. 22, 2010)

A metal door with lock, above, separates the west courtyard of the North Quad from the Ventura Street building yard, seen in the photo below. The top photo is the north side of

the door, in a locked courtyard, and the photo below is the south side of that same door, in another locked courtyard. One of the weird things about Camarillo is all the outside gates and doors are heavily locked. (Photos: K. Anderberg, Jan.21 and Feb. 21, 2010)

A metal door with lock, above, separates the west courtyard of the North Quad from the Ventura Street building yard, seen in the photo below. The top photo is the north side of

the door, in a locked courtyard, and the photo below is the south side of that same door, in another locked courtyard. One of the weird things about Camarillo is all the outside gates and doors are heavily locked. (Photos: K. Anderberg, Jan.21 and Feb. 21, 2010)

Outer walls at Camarillo Hospital...

Outer walls at Camarillo Hospital...

Thank you to Resist.ca for hosting this website!